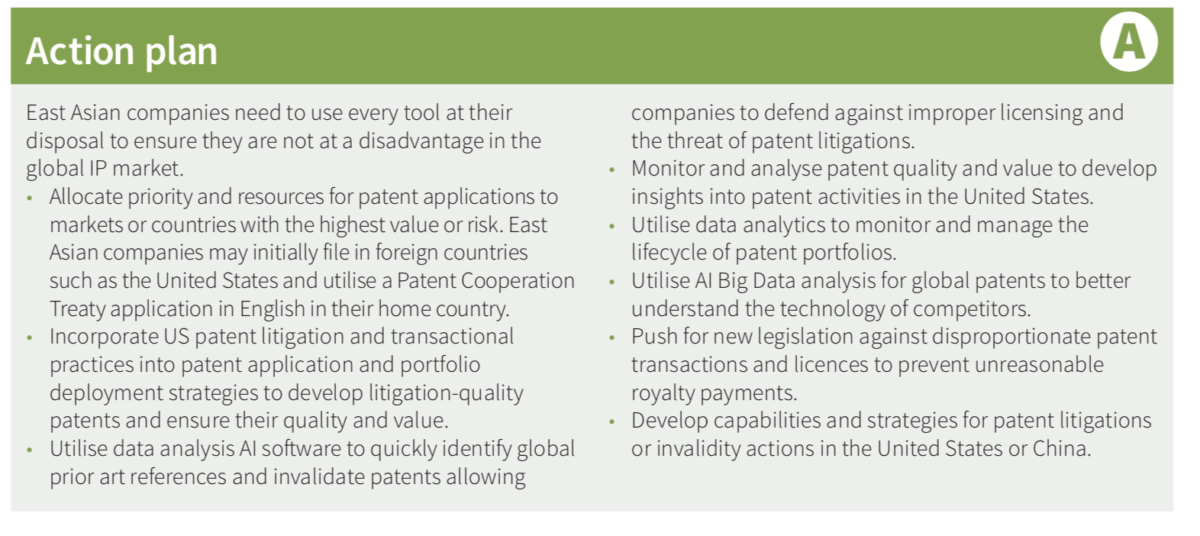

October 2018 – A turbulent IP and trade environment has Asian tech firms caught in the crossfire. They need to use every tool at their disposal to protect their businesses

Since the enactment of the Trade Act of 1974, the United States has investigated and imposed trade restrictions on several countries and numerous companies in East Asia, starting with Japan in the 1970s, Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong in the 1980s and China in the 2000s. Increasing exports from East Asia led to the United States making allegations of unfair trade practices against Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong for IP infringement and counterfeiting, and against China for the theft of intellectual property and trade secrets.

With the introduction of Section 301 of the Trade Act and Section 301 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, IP rights began to play an increasingly significant role in world trade, prompting countries and their leaders to promote legislation and judicial administration to protect intellectual property. Nonetheless, US companies continue to rely on the International Trade Commission and federal courts – under Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930 and 35 USC Section 271 – to ban imports and sue for payment of damages against imported goods from East Asia. In addition, with the Economic Espionage Act of 1996 and the Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016, more companies and individuals in East Asia are facing accusations of criminal and civil liabilities in the United States.

Licensing negotiation: retake the initiative

Companies in East Asia often face threats of patent litigation and unfair licensing terms. Rather than blindly submitting to such practices, companies should develop strategies and mechanisms to analyse data in order to assess the quality and value of a patent portfolio. Patent quality, value and price are distinct qualifiers in evaluating a portfolio. IP professionals would likely agree that quality is the foundation of patent assessment and this is based on satisfying the requirements of 35 USC Section 101 (utility and eligibility), Section 102 (novelty), Section 103 (non-obviousness), Section 112 (adequately described) and considering the lack of prior art referenced during the prosecution of the patent. All granted patents are deemed to have met these requirements by USPTO and presumed to be valid. If a claimed invention comprises eligible subject matter, is useful, novel, non-obvious and described with clarity, the patent will at the very least possess a baseline quality. This quality increases if the claims are carefully crafted to ensure accuracy and logic while maximising the claim scope and increasing the difficulty for competitors to design-around. It is essential to precisely summarise the technology within its technical field and respective industry, determine the claim scope and use a combination of independent and dependent claims to maximise the patent coverage to include all foreseeable alternative embodiments. In certain circumstances, multiple filing of related patents is necessary.

Patent value extends beyond the extent of the patent and considers its commercial viability, the market conditions and industry position. Whether the covered invention has market demand determines whether the patent has any value. A heavily researched and well-written patent may meet the various patentability requirements, however, it may have very little value because the covered invention is outdated or for an obscure technology that interests only the inventor. This is the reason why most patents fail to hold any market value. Patent value can be reflected in:

- industry position, value proposition and physical evidence;

- commercialisation activities associated with the patent, the degree of industrialisation and the profit generated;

- patent licensing and other memorisation activities;

- the amount invested in the development of the patent; and

patent infringement activities and the amount of compensation from these activities.

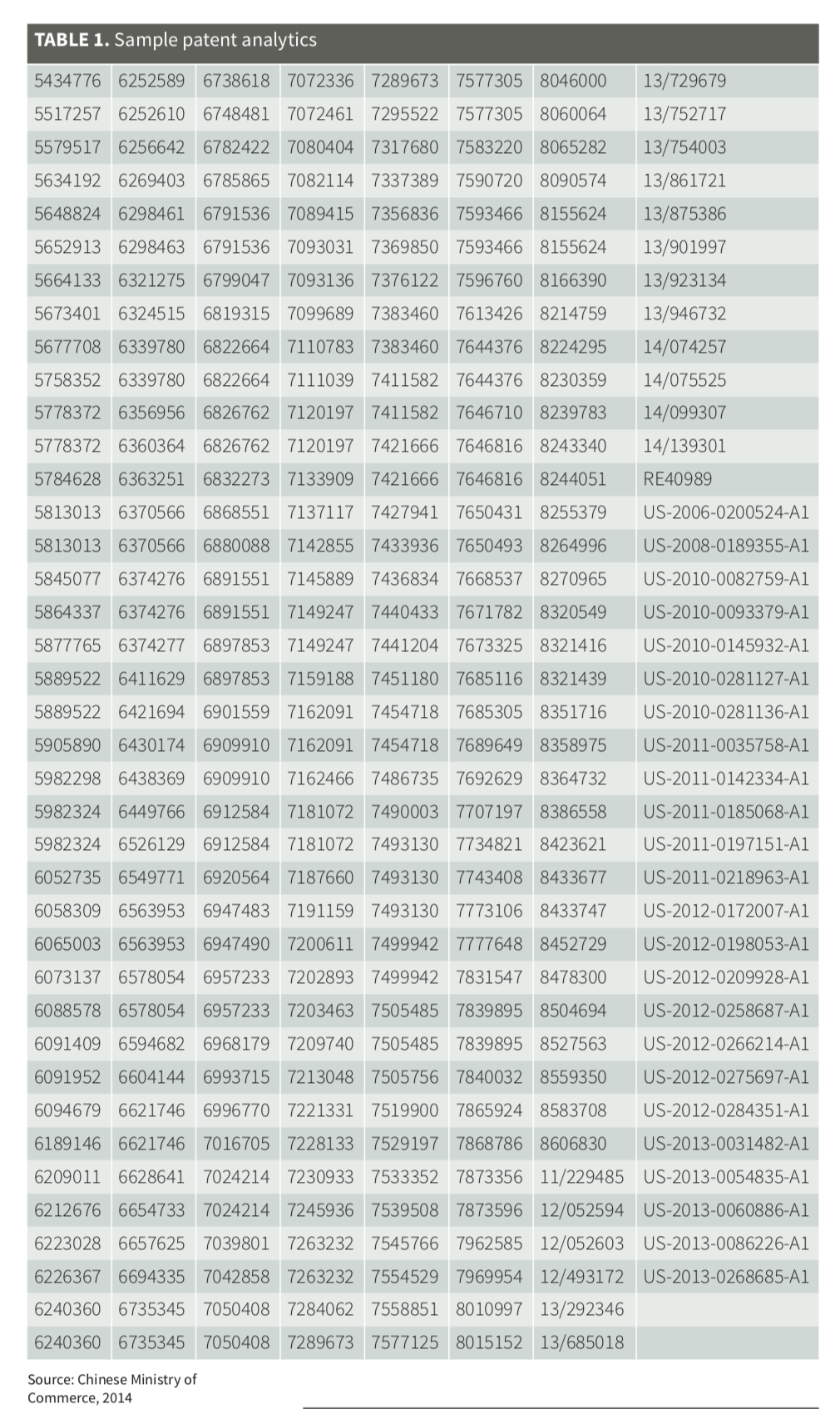

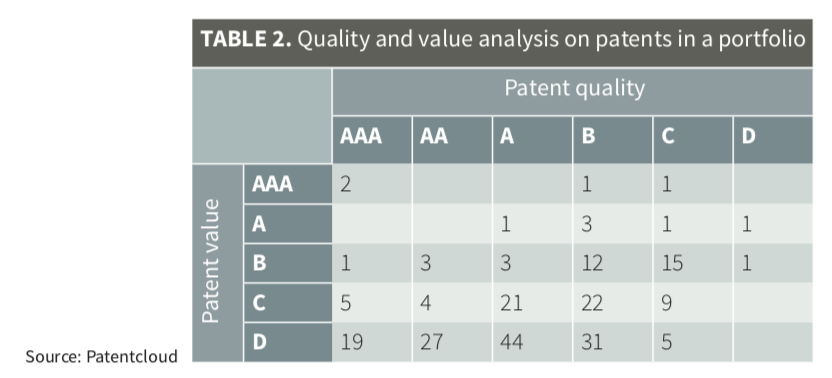

An evaluation of 300 patents in a portfolio revealed that the majority of the patents were of average quality and value (see Figures 1 and 2).

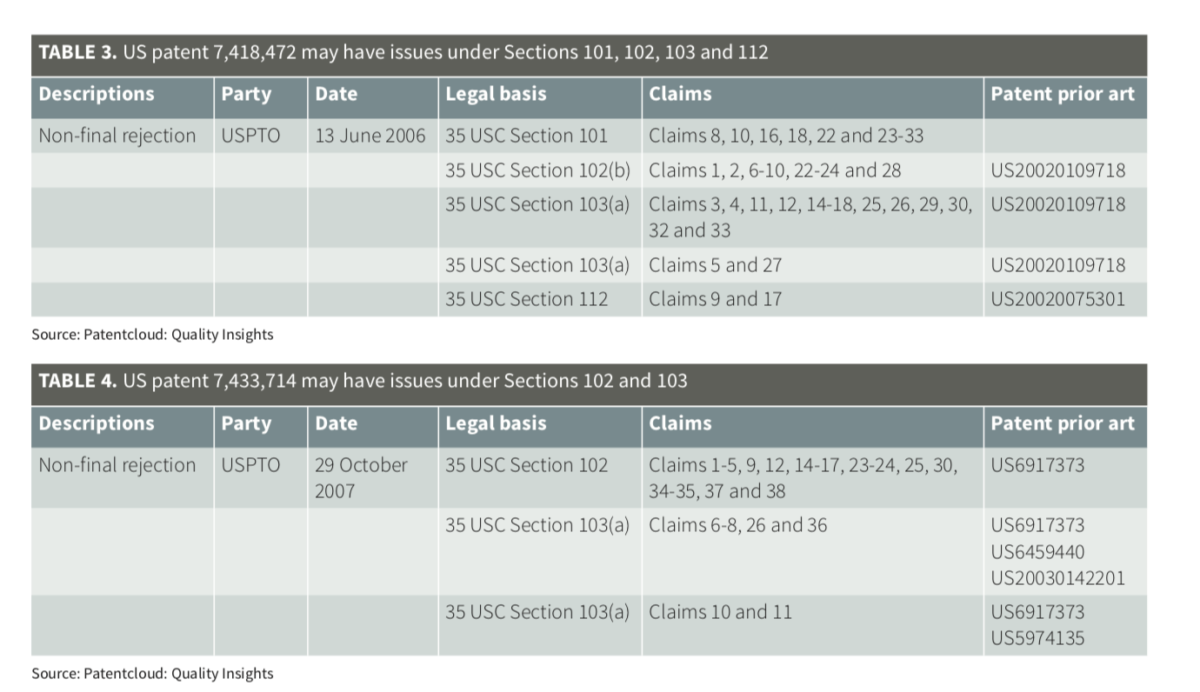

The value of this portfolio would be negatively affected if the few quality patents it contains could be invalidated. Valuable insights for invalidating a patent can be revealed through the analysis of a patent’s prosecution history (see Figures 3 and 4).

During the prosecution of these patents, the patent prosecutor raised non-final rejection issues with certain claims and identified potential prior art references. Such information can be useful in evaluating the patent’s quality.

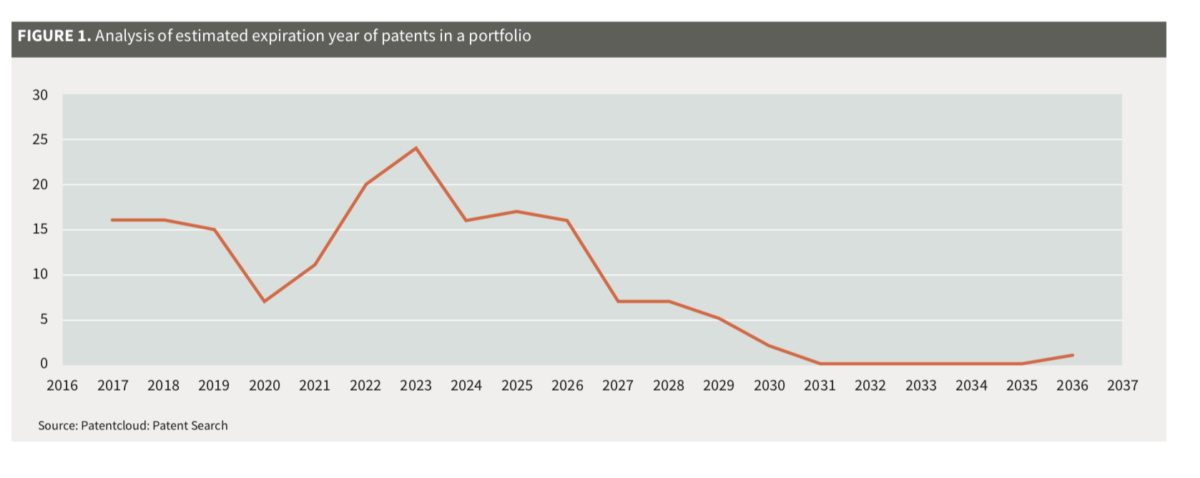

An overview of the estimated expiration date of the patents in this portfolio showed that most will expire by 2023 (see Figure 5).

Potential licensees of this portfolio should take this information into consideration when considering a licence. Arming themselves with such information puts companies in a better position to negotiate against threats of patent litigation and unfair licensing terms.

Licensors often combine a small number of patents with evidence of use with a large number of inconsequential patents as part of a portfolio licensing programme. The licensee may be prejudiced by this type of licensing scheme if the ratio of the patents relevant to the licensed product is nominal (eg, if the ratio of patents that cover the licensed product’s dominant country is relatively small compared to the rest of the portfolio). Without transparency and tools to analyse a patent portfolio, licensees may be paying large amounts of royalties for a portfolio that offers little to no value. Armed with such IP management and analytics capabilities, the licensee is in a better position to negotiate a fair licensing fee.

Playing catch-up: how to build a quality portfolio

There are few East Asian multinational companies with the resources and IP prowess to professionally manage quality patent portfolios. This lack of investment to develop quality patents opens the door to criticism by the United States and allegations of technology theft, despite the fact that theft is only legally applicable to trade secrets – patents, copyrights and trademarks are publicly accessible. Technology theft is less likely to be an issue if a company’s business culture cultivates an ethical responsibility against counterfeiting, plagiarism or theft of trade secrets. Even with invested resources, most companies have mistakenly placed their focus on the quantity of US patents, rather than quality. As a result, many East Asian companies’ patent portfolios are of poor quality and low value, which means that they cannot compete with their US counterparts. With the aid of government funding during the past decade, Chinese companies have significantly grown their patent portfolios in China; however, the majority of these patents are still lacking in quality.

The lack of development in quality patents remains an issue among East Asian companies. Development of quality patents requires investment in R&D and professional expertise in areas such as IP law, translation of technology into patentable expressions, language translation and a standard operating procedure management system. Priority and resources for patent applications should be allocated to markets or countries with the highest value or risk (eg, the United States), a company’s home country is not necessarily the best place for a first patent filing. Certain East Asian companies should consider an initial filing in foreign countries such as the United States and utilise a Patent Cooperation Treaty application in English to file in their home country.

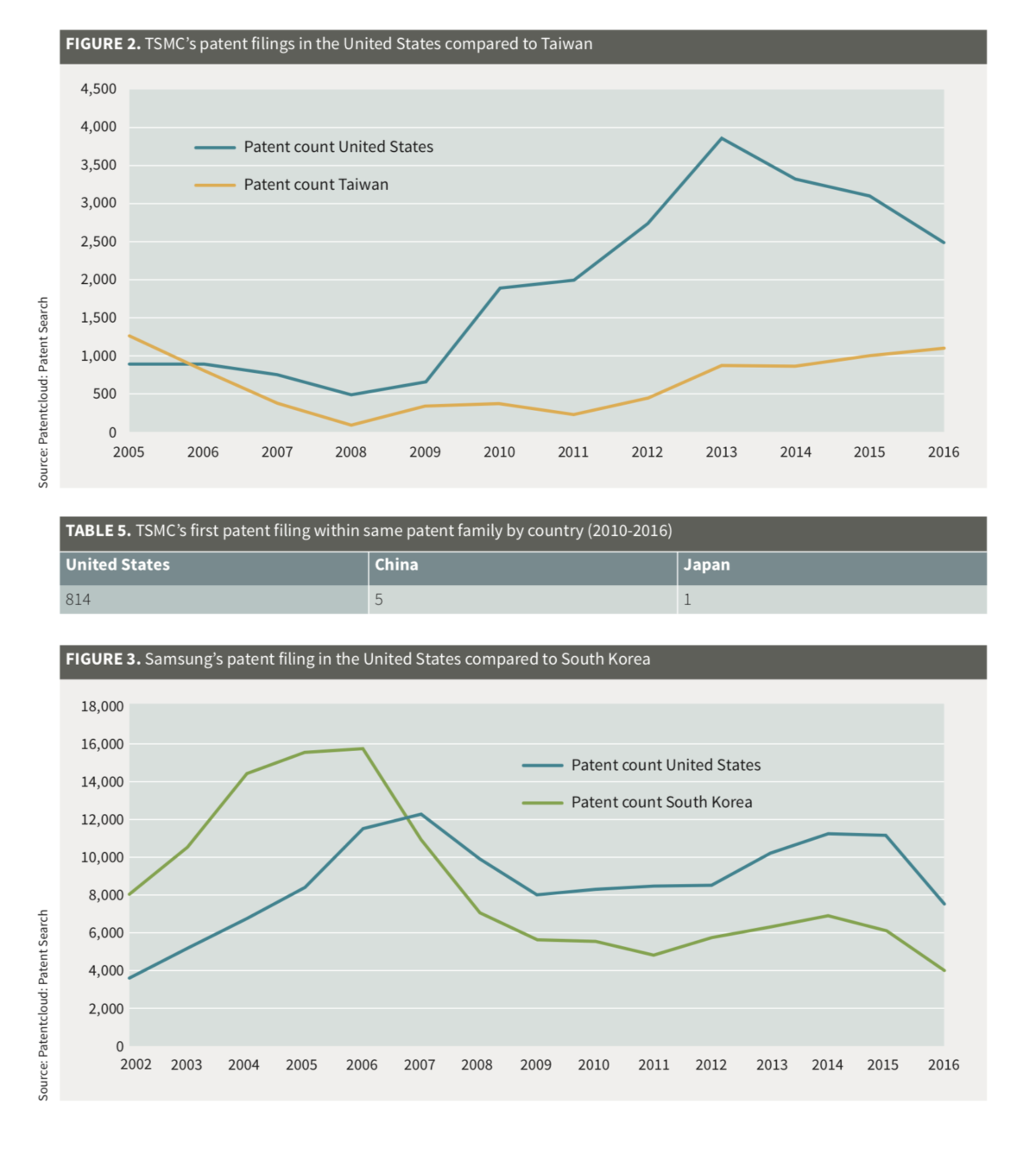

Since 2010, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation Limited (TSMC) has climbed the charts in its patent filings in the United States. Since 2005, TSMC has shifted its focus from filing patents in its home country to the United States (see Figures 6 and 7). This strategy adjustment became apparent in 2010 when the company’s US patent filings grew exponentially, while its filings for Taiwan patents remained stagnant.

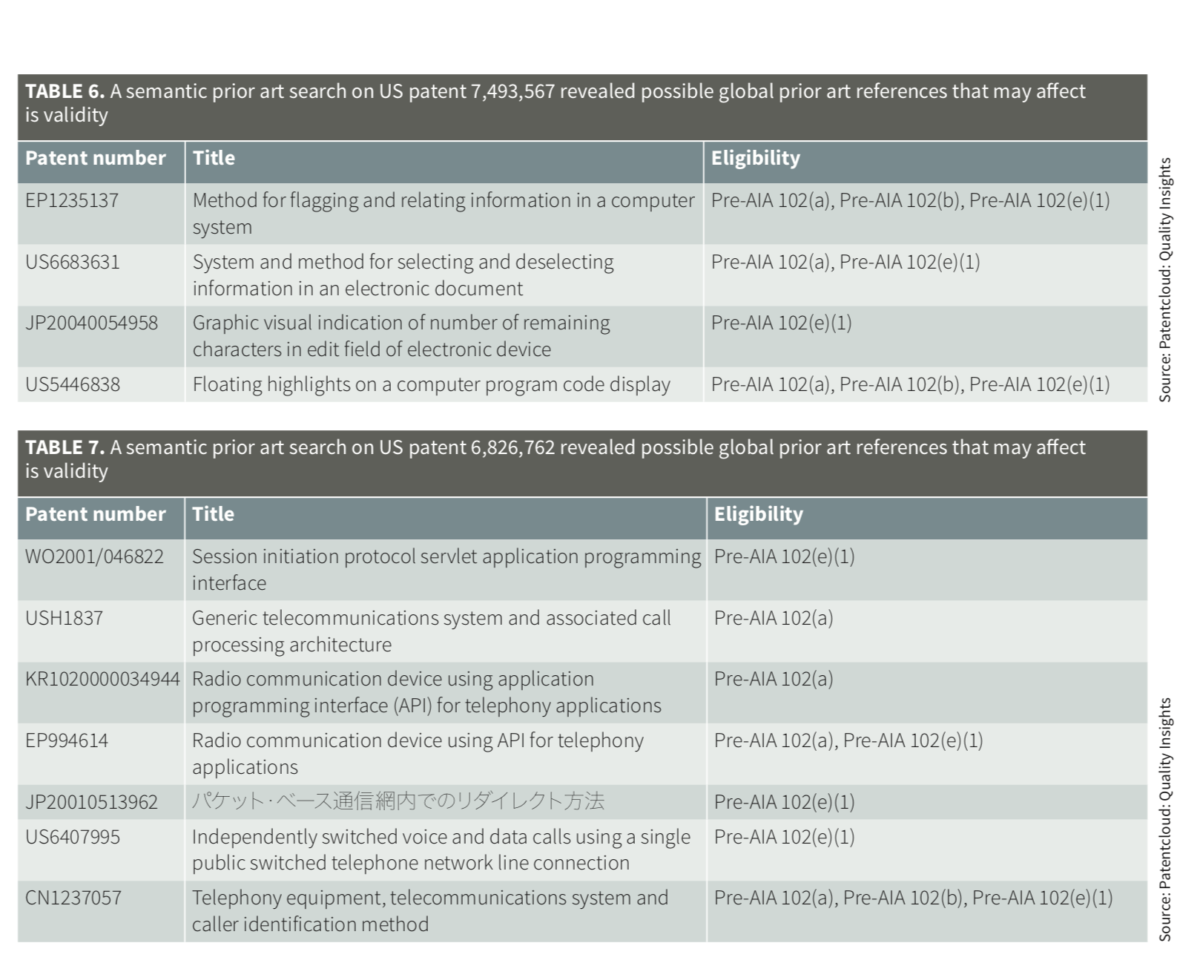

Similarly, since 2007, Samsung Electronics has invested more resources in its display patent applications in the United States (see Figure 8).

Avoiding patent minefields

Even if a company has no intention of infringing a patented technology, it is not uncommon for it to unintentionally fall victim to patent mines. East Asian companies should arm themselves with patent infringement professionals and invalidity actions and actively file litigations in the United States or China. More than 60% of patent claims involved in infringement litigation may be invalidated or deemed unenforceable. With artificial intelligence (AI) Big Data analytics technology, global patent portfolios can be quickly evaluated and prior art references quickly identified. In one example, a semantic prior art search revealed possible global prior art references that may affect the validity of essential patents (see Figures 9 and 10).

A prior art search is a task that traditionally requires a skilled team of IP experts several days to perform. With recent advancements in AI and Big Data analysis, prior art searches can now be completed within a fraction of the time. Such information can not only aid companies in East Asia against pressure from US counterparts, but it can also be used to strengthen patent portfolios. Developing litigation-quality patents and robust portfolios requires Big Data analysis for patent application and deployment.

East Asian governments should create their own strategies for IP deployment, protection and monetisation rather than implementing a system tailored for US companies. Adopting IP policies based on foreign systems may inadvertently protect foreign companies more than East Asian companies. Therefore, to compete and excel in the global market, East Asian governments and their companies must create innovative IP strategies separate from the US equivalent.

“This article first appeared in IAM Issue 91, published by Globe Business Media Group – IP Division. To view the issue in full, please go to www.IAM-media.com”